Smart People, Difficult Software: A Cultural Problem

Oct 31, 2025

Imagine, you sit down at your computer, open a chemistry drawing program for the first time (naming no names), and stare at a wall of cryptic icons and menus. You're a smart person-you have a PhD, you've read thousands of research papers, you can decode complex experimental methodologies. But right now, you feel a bit less than. You need the manual to draw a simple benzene ring. Everyone around you seems to understand what to do. Why do you seem to be the only one who can't use this thing?

In my opinion the problem isn't you. The problem is that scientific software is built by very clever scientists and engineers who have had to "just figure it out" with regards to every tool and paper they have encountered in the past. We have a blindspot where we think software tools that do something complicated need to appear so. This creates a peculiar situation where the most sophisticated tools are often the hardest to use - preventing adoption from large numbers of potential users.

The Cultural Problem: We're Trained to Figure Things Out

Scientists are trained differently than most people. We're conditioned to:

Read dense, jargon-heavy papers without complaint

Figure things out from first principles rather than asking for help

Never admit we don't understand something, leading to imposter syndrome

Value complexity as a signal of sophistication and thoroughness because we have always moved from a position of ignorance to understanding in our training.

Assume that if we can understand it, anyone in our field should be able to as well. We could say this is almost like some kind of generational trauma in scientific training. I went through this so it is expected and normal

This training in resilience can serve us well in research, but it can create a blind spot when building software. We may approach software design the way we approach research problems, by assuming our users have the same tolerance for complexity and the same "figure it out" mentality that we do.

In my experience in scientific cultures, nobody wants to look like they don't get it. So when faced with (let's be kind) suboptimal software UX, we don't complain. Instead, we may assume it's our fault for not being smart enough. This creates a feedback vacuum where usability problems never surface.

The interdisciplinary nature of scientific software teams could make this worse without a psychologically safe environment. When you have domain experts, software engineers, product managers, and designers all working together, nobody wants to be the person who admits they can't figure out the interface. The biologist doesn't want to look technically incompetent. The engineer doesn't want to admit they don't understand the scientific workflow. Everyone stays quiet about usability problems rather than risk looking incompetent outside their area of expertise.

This silence protects everyone's professional status while ensuring the software remains unusable. I would argue that our companies often have a culture where admitting confusion feels like undermining your credibility, so honest feedback about user experience gets suppressed. This is more of an observation of an area for improvement - by simply improving communication within and between development teams and users we could vastly improve software usability in life sciences.

How This Breaks Software Design

This cultural conditioning creates several problems when interdisciplinary teams build scientific software:

The "If I Can Figure It Out, Anyone Can" Fallacy

Scientific software creators vastly underestimate the learning curve for their tools. We've spent months or years building the software, we understand every button and menu. Maybe we can't imagine why anyone would find it confusing. We might forget that domain expertise doesn't automatically translate to software expertise.

As a recent example for me I would refer to the gnomad browser. Gnomad itself is a wonderful datasource with comprehensive coverage of genetic variants from academic publications. However, I find the user interface unintuitive. Perhaps I am not the intended user. The constraint data is most interesting to me, but I feel like need to be a grad' student in statistical genetics to understand and interpret the data properly. Gnomad is primarily a source of data - not a workflow based tool, but there is enormous opportunity to make more use of the data simply by delving into the types of questions that "potential" users may have and building user journeys around them. Given the data comes from tax dollars/euros, it would be responsible to unlock value form the data in this way for relatively little cost.

Complexity as a Proxy for Quality

In scientific culture, complicated often equals impressive. We're used to solving hard problems, so we may have a bias that conflates software complexity with the complexity of the user's problem. If the science is sophisticated, then we might assume the software should look sophisticated too.

This can lead to user-interfaces that show everything at once - every possible analysis option, every piece of metadata, every advanced feature. The reasoning being something like this: "Look at all the things we can do! Surely that's valuable!" But for users, it's probably overwhelming and it could hurt adoption. Nobody wants to feel dumb when presented with presumably important and essential options without understanding how they work... Then users go back to their default manual processes.

No One Wants to Build the "Simple" Tool

In academic environments, I would say building the "simple" version of something doesn't get you citations or conference presentations. Simple doesn't feel impressive because it is within the grasp of most users. Simple doesn't feel like it demonstrates your technical prowess or deep understanding of the field. Don't we want to show off a bit?

So we end up with tools that are built to impress other scientists rather than to help users get work done. The goal may unconsciously become showing off capability rather than solving problems efficiently.

We may end up with software that looks impressive in presentations but feels like punishment to use.

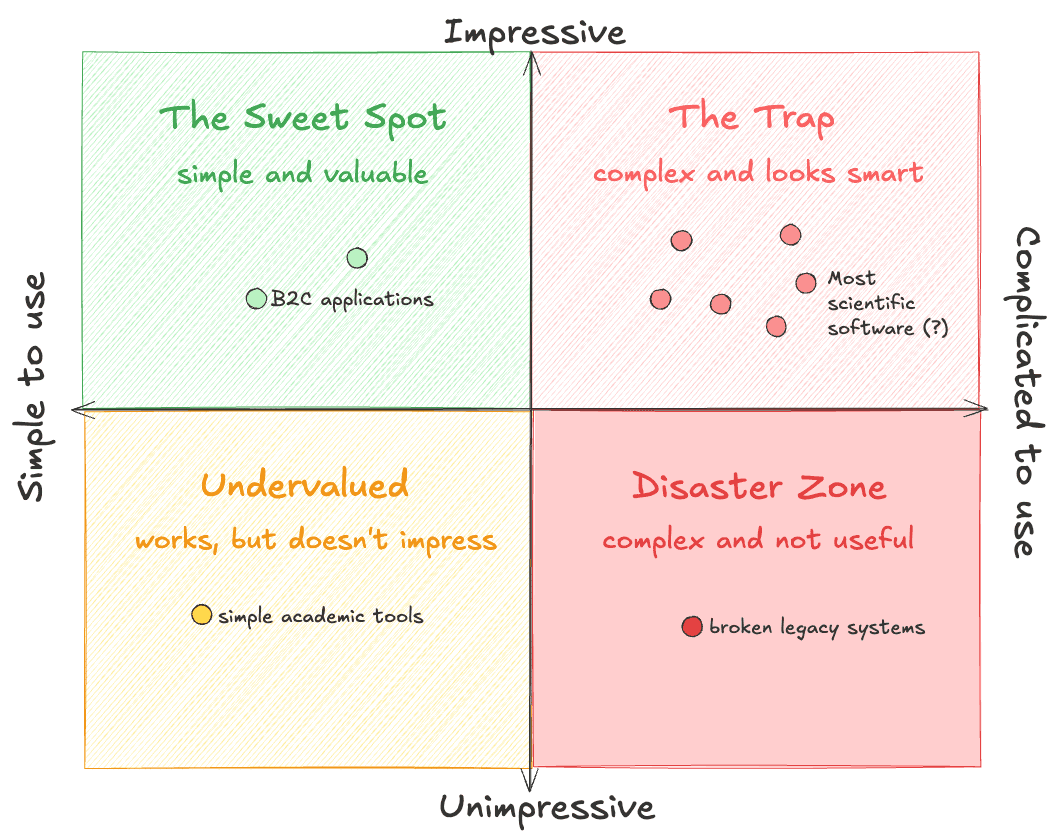

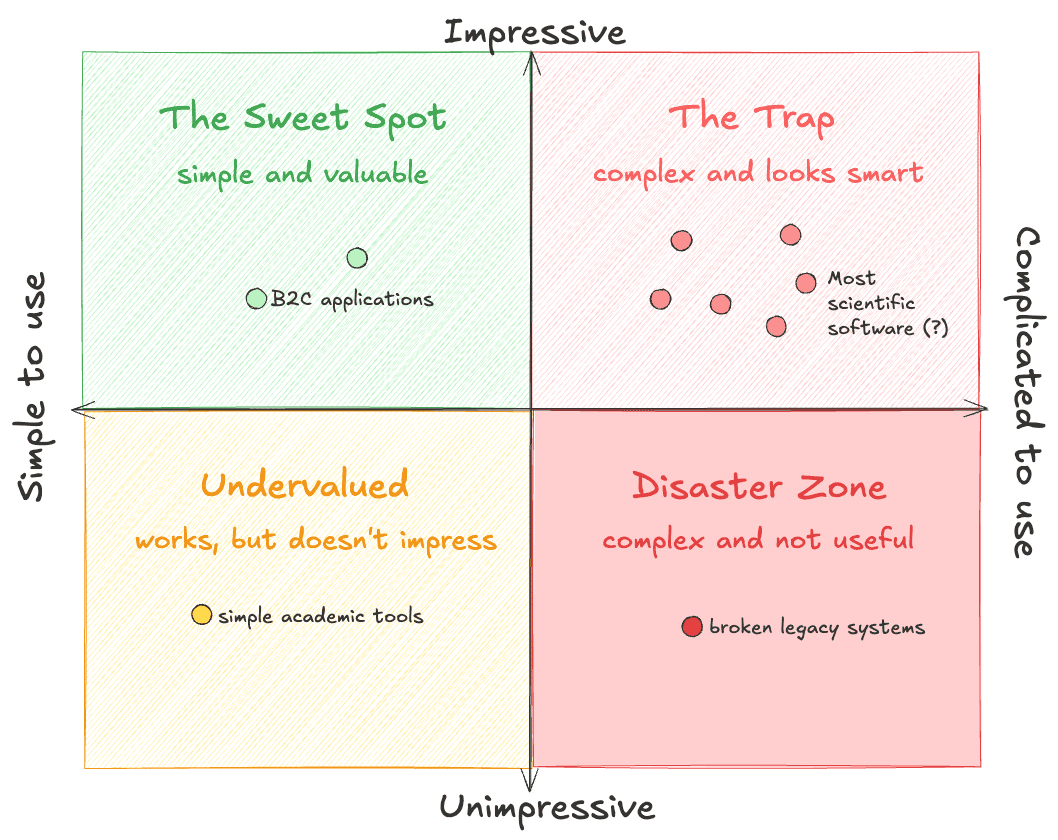

How I think about the conflation between complexity and value

Why This Hurts Science

This approach to software design could stifle scientific progress

Tools don't get adopted: When software is too complex to learn quickly, people may stick with familiar tools or manual processes, even when better options exist. This is a crazy marketing issue - the core function of the tool may be excellent, but the UX is so bad that users cannot make the leap.

Time gets wasted struggling with interfaces instead of research: Researchers spend hours clicking through menus and deciphering interfaces instead of thinking about their actual scientific questions.

Barriers to entry increase: Complex software creates gatekeeping effects, making it harder for new researchers or people from different disciplines to contribute.

A Better Way Forward?

Scientific software doesn't need to be revolutionary or look complicated to be valuable. It needs to be dependable, clear, and designed for real work. It can even just solve very simple problems. If we expand our view out to other businesses we can see Slack, Salesforce, and SAS have built empires from fulfilling rather mundane business needs. Here's what that a simpler approach may look like:

Break Down Workflows Into Manageable Stages

Instead of showing everything at once, guide users through a logical sequence. Scientific reasoning, especially where there is a well-defined question, follows patterns. We can design workflows around those patterns, introducing data and options at the right time to reduce the users' cognitive load.

Create Guided Workflows for Common Use Cases

In early pharma R&D, target validation is a different exercise than indication expansion, but they might use the same tools configured differently. Instead of making users figure out the right configuration, we can guide them to the most appropriate setup for their specific problem. This approach will also help reduce the number of options available to users at any one time and help them more easily learn how to use the tool.

Help Users Understand Where Evidence Comes From

Showing a confidence score for some evidence is okay, but users need to be able to inspect how that score was calculated and based on what data. This is especially important in scientific software where users need to evaluate the reliability of information.

For example when finding evidence to support a disease-gene relationship we probably also want to know the level of consensus on the direction of the relationship within the literature.

Simple Can Be Sophisticated

The goal is to make scientific software simple to use, not make it simplistic. There's a difference between reducing functionality and reducing friction in daily use. Good design lets users focus on thinking, not clicking.

For scientific software builders, a user-centered approach could improve adoption, build trust, and ultimately lead to better scientific outcomes.

Good User-centric thinking in the wild

Recently, I saw a good example of user-centred improvements which worked by simplifying the user journey. Dotmatics recently updated their ELN based on user feedback about various things that were suboptimal in daily use. Users said entering process design data was laborious, so they improved the ergonomics, and now it's single-click instead of multiple clicks. I would not underestimate how much this will improve the experience of dotmatics ELN users - a small tweak can vastly improve adoption.

The team identified and fixed a strange situation in the software where bench scientist users couldn't move consumed containers in their dotmatics system directly to trash while checked out; they had to check them back into the inventory first. But, in reality nobody returns empty reagent containers to the store before immediately throwing them away. Dotmatics changed the software to match how people actually work.

These aren't massive feature overhauls, but they are quality of life improvements that show someone listened to feedback, and cared about user satisfaction. This kind of empathetic design is exactly what we need more of in scientific software design.

Wrapping Up

Scientific software doesn't need to look complicated to be valuable.

The challenge with scientific software isn't that any individual group is bad at building tools. Our cultures may make honest feedback about usability feel risky. To me, it feels like we're building tools the same way we approach research problems, assuming everyone else has the same tolerance for complexity and the same "figure it out" mentality.

Software design requires empathy with the users. Even very smart people shouldn't have to decode our user interfaces like they're reading a rather dense methodology section.

Software that looks clever might just be software that no one wants to use. The most sophisticated tool in the world is worthless if it sits unused because the learning curve is too steep. Our goal should be building tools that let scientists focus on science, not on deciphering interfaces.

Having the confidence to appear dumb with simple, but useful software design may be a very useful strategy in helping our users, gaining adoption of our tools, creating medicines and driving revenue. I encourage the Product People and designers to have the confidence to be the "dumbest one in the room". It might help us create a safer environment and better, more useful software to serve scientific work.